Do you remember how life used to feel?

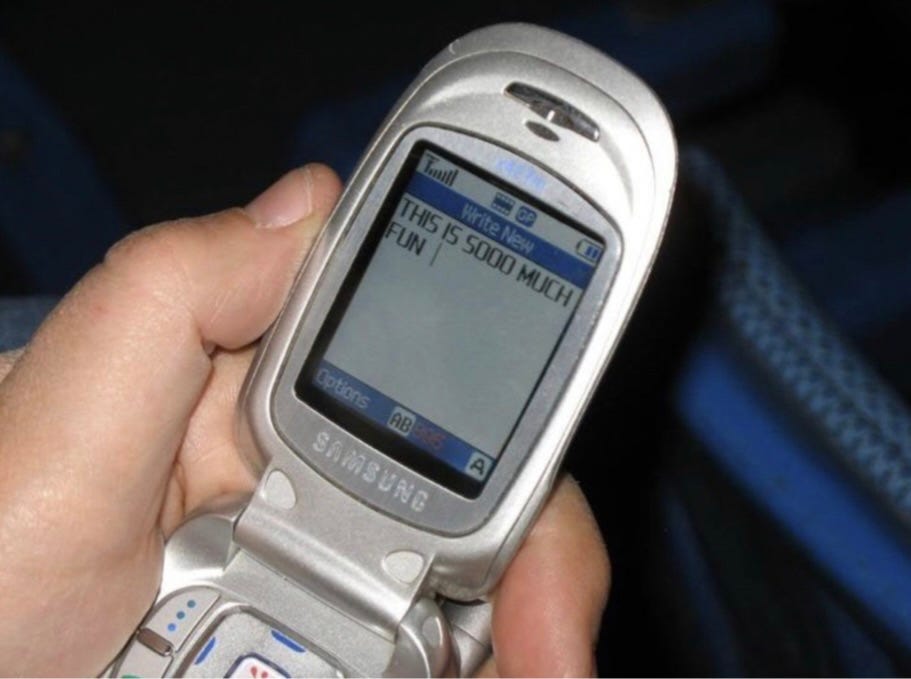

Flip phone February: how I downgraded my phone and upgraded my life

In this post, I share how I finally broke my smartphone addiction.

If you want to read the whole thing, which outlines my own personal approach to downgrading, what flip phone I bought, and what I do for everything from maps to photos, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. A paid subscription also gives you access to my popular guides on setting goals and making the most of your 20s, 30+ essays in the archive, and audio Q&As.

I owe a great deal to writer, painter, and anti-tech activist

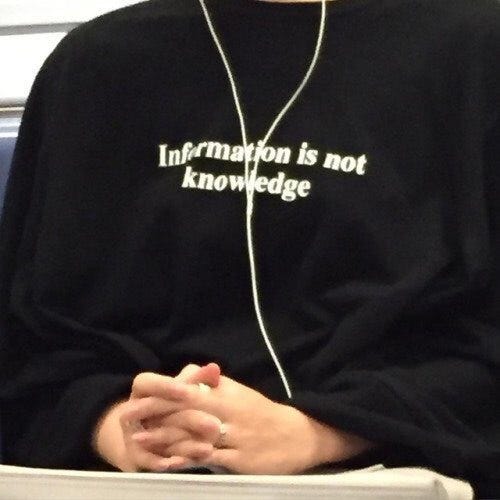

, who inspired me to downgrade and wrote a terrific guide, You don’t need a smartphone: a practical guide to downgrading & reclaiming your life. You can purchase it here.I claimed to be a victim of my phone—an inanimate object I could, in theory, toss into traffic—for literal years, maybe even a decade, because I didn’t want to sit down and think seriously about how to change my life. I didn’t want to feel even a little bit of friction. My phone offered me so many “benefits,” so much “convenience.”

These days, we’re all pretty good at the sales pitch, rattling off the benefits of something. We’re not great at a clear-eyed interrogation of the costs. I think this tendency comes from a good place—a desire to be optimistic—but this means we’re constantly overstating the benefits, downplaying the costs, and wondering why things are not as good as we hoped they would be. Yes, smartphones offer countless benefits, but the cost of smartphone addiction is enormous, tremendous, and far too high (literal years of your waking life).

I have been without my smartphone for a month and my life is so much better I can hardly find the words. It’s painful to admit: up until now, I’d been complaining about the handcuffs around my wrists while simultaneously holding the keys. Do the corporations who engineer these devices and apps to be as addictive as possible deserve our scorn? Yes, they do.1 But we also have free will. You can move to Italy. You can quit your job. You can decide to buy a flip phone and actually use it.

You really can. Here’s how I did it.

Step one is admitting you have a problem

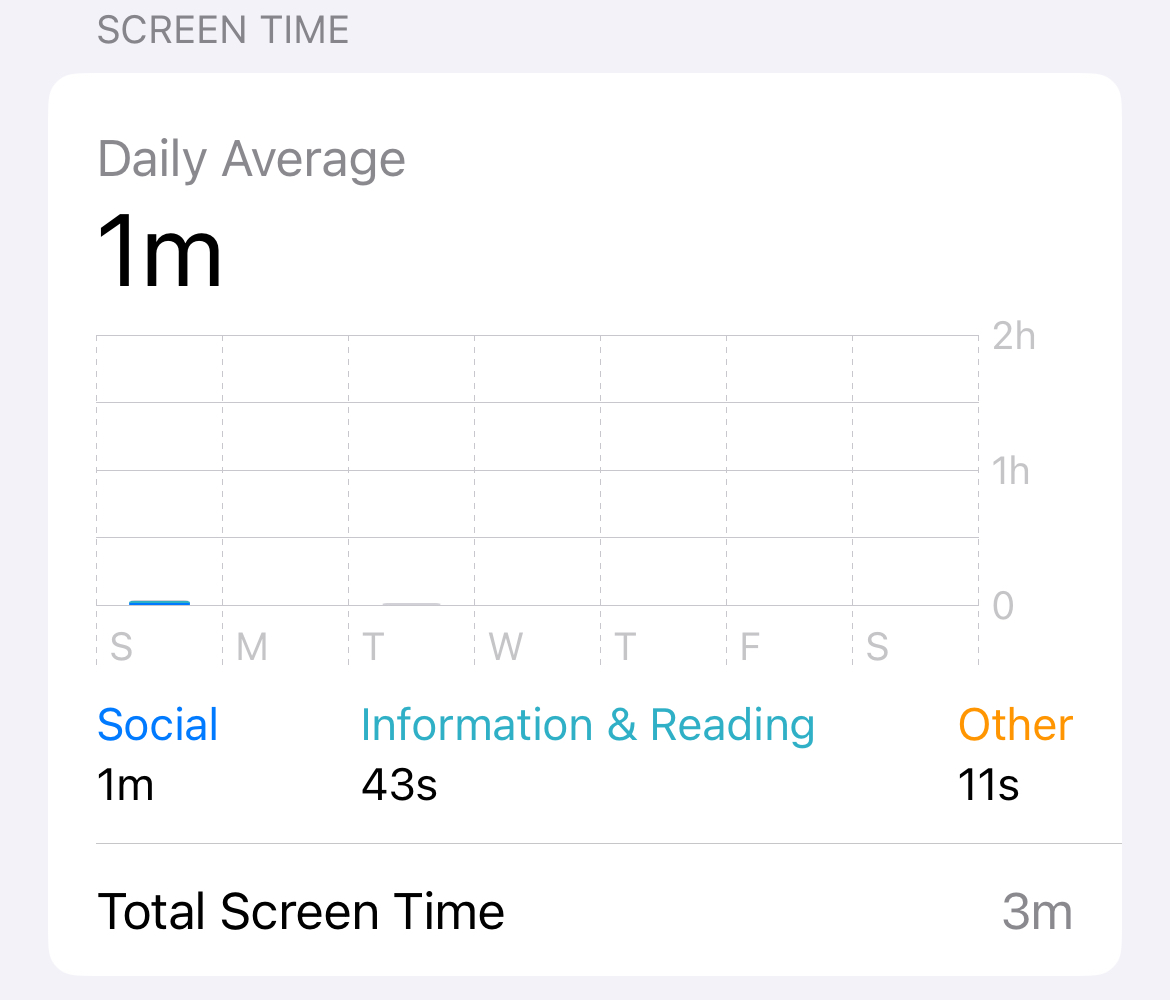

I wrote about how smartphones are hollowing out our lives in my essay, Your phone is why you don’t feel sexy. I re-read that essay recently, and honestly, it made me feel like a hypocrite. Not only had I come up short on offering practical solutions for smartphone addiction (I offered none), but here I was, vilifying the smartphone, something a thousand people have done, and yet I still spent hours on mine every day. When I wrote it, I was nine months pregnant and sure that I would use my phone less once the baby arrived.

I was wrong.

I scrolled a bit before bed, sometimes in the middle of the night after I fed my son, and often first thing in the morning. More often than I’d like to admit, my husband would ask me a question, and I’d have to ask him to repeat it, sometimes twice, because I was sucked into the void of my phone. I felt my phone’s constant pull—and its maddening, mind-scrambling distraction—when I was meant to be present with my family. Often when I was most exhausted or stressed, I wanted to curl up in bed and “go on my phone.” This drained me further.

All of this made me—makes me—feel ashamed. Shame is a hard emotion to deal with, and often, our first reaction to feeling shame is to double-down, even if we know what we’re doing is wrong. I’ve known I’ve had a “phone problem” for years, but I’ve always attempted to rationalize it to myself.

A few of my many excuses:

“This is how everyone lives now.” (A lie.)

“I’m not as bad as other people, some people are on their phones for like seven hours a day.” (Like I have never done that before.)

“I’m reading.” (Twitter.)

“I’m urgently looking up information essential to my or my child’s well-being.” (I’d probably find the answer more easily on desktop. And if it’s truly an emergency, you don’t look it up on Google, you call the doctor or 911.)

“I’m working.” (Scrolling Substack Notes.)

“I need to stay connected to what’s happening in culture.” (As if I cannot read and do not own a computer.)

“I’m looking at photos of my son.” (When he’s right in front of me.)

“I’m catching up with people.” (Reading a text and marking it unread in order to reply later.)

“I’m learning.” (Half-listening to a podcast or YouTube video.)

These are the words of an addict. The only legitimate excuse is that these devices and apps are quite literally designed to keep you on them. Some of the brightest minds of my generation have literally devoted their lives to getting people—getting you—to stay on the apps and click ads, monetizing your time and attention for their own benefit.2 We’re all doing a terrific job funding their Tahoe houses and sumptuous dinners overlooking the San Francisco Bay. It’s really depressing. Now that I’ve been without my iPhone for a month, the amount of information and stimulation I subjected myself to on a daily basis astonishes me.

An embarrassing review of previous attempts to free myself from my phone

This is my fifth attempt to break my smartphone addiction, and the only one that worked. It’s probably worth noting that I’m a pretty disciplined, principled person. I don’t say this to brag; I say it to emphasize just how challenging it is to break free from the phone. Despite being able to successfully set limits and rules in all other areas of my life, before now, I have never been able to resist my phone for more than a day or two.

1st attempt • Deleting the apps + greyscale • 2019

I deleted the time-wasting apps, like Instagram, and put my phone in greyscale. But I would still check social media on my phone’s browser, eventually re-download the apps, and take my phone out of greyscale to “watch a video.” Then I would conveniently “forget” to put it back in greyscale. This attempt was kind of a joke, even to myself.

2nd attempt • A second, dumber phone • 2020

I purchased a second phone off eBay—an old 2013 Blackberry Classic. I chose this phone for the physical keyboard and lack of touch screen. On my Blackberry, I could check and respond to work email (I had an “always on” corporate job at the time), make calls, and text. But Blackberry stopped supporting these devices and their software, so when the networks got upgraded, it flat out didn’t work anymore. This plan didn’t work that well anyway: I would often bring both my iPhone and my Blackberry with me, in case I needed to “take a picture.” Sometimes I would just cut to the chase and only bring my iPhone. When I had a choice of which phone to use, I always went with the more “enjoyable” one (that also happened to have Instagram).

3rd attempt • iPad baby • 2023

I decided to set app limits, which I constantly overrode to the point of parody. I may have even spent more time on my phone with app limits, because it was always “just 15 more minutes.” Do this four times a day, and that’s an hour. Then I had my husband set a passcode I didn’t know, so I couldn’t override them. But, like an iPad baby, I always asked him for “more time,” sometimes several times a day, under the guise of “checking my notifications.” This put him in a bind and was annoying of me. When he traveled to Europe for a show, the limits were off, and I would spend tons of time on my phone. This did not work.

4th attempt • Physical separation • 2024

Last year, I declared that my phone “wouldn’t leave the kitchen unless I left the house.” I could check my phone in the kitchen, but I wouldn’t scroll because “there’s nowhere to sit down in the kitchen.” I also told myself I wouldn’t scroll when I left the house because I was “doing stuff.” I was wrong, of course—I did scroll—and I often just took it out of the kitchen with me. There was always something “important” I needed to do, a photo I needed to take, etc.

Sometimes it just takes one small thing to make you realize the way you’re living your life is no longer sustainable. In my case, it took three.

I’ve read entire books about phone addiction and countless articles about “The Problem with The Phones”—I even took it upon myself to write one—but the combination of these three things hit me harder than any of it:

1) If you spend 3 hours a day on your phone, it ends up being 10 years of your waking adult life.

Read that again. A decade of your waking life. Think about how long a year is. Now think about how long ten years is. Now imagine spending all of that time, ten years of your precious adult life, watching TikTok and bouncing between candy-colored icons on a metal rectangle. Now try not to throw up.

If I allow myself to internalize this, I find it simply unbearable. The clock doesn’t start when you’re seventy, by the way. It starts now. I cannot imagine watching ten years of my life go by instead of being present with myself, my husband, and our son. But that’s what would happen if I didn’t make a radical change. I learned this fact from August Lamm’s guide, where she puts it better than I can:

“Imagine looking back over your life and watching ten years’ worth of footage: you at various ages holding a smartphone, scrolling, rapt, pacified, oblivious to your surroundings, to all the things you are choosing not to do, to all the sides of yourself you don’t know because you’ve surrendered to your smartphone the time it would take to discover them. Is this how you want to spend your life? This is how you are spending your life.”

2) My infant son doesn’t know his own name, but within a few months of his life, he understood my iPhone as an object of great importance to me.

I don’t think I need to explain how depressing that is. Two things happened with my baby. One, he reached for it, spellbound, whenever he saw it. And two, I was doing something unimportant, scrolling, and I looked up and saw he was smiling at me. This had happened a few times before—and countless times when I’m doing other things, like the dishes—but this particular instance stung in a way I can’t quite explain. If I didn’t make a change for myself, I should at least do it for him. The last thing I want to be in his eyes is a hypocrite.

3) In a discussion about phone addiction, my husband casually said to me: “Scrolling on your phone and wondering what other people are doing instead of living your own life is loser behavior and I’m done with it.”

My husband is the most disciplined person I’ve ever met. When he decides he’s done, he’s done. He doesn’t check his phone that often, and never scrolls (imagine). So, shoutout to him. He’s also correct.

When it comes to phone addiction, my biggest issues are: (1) proximity to a handheld, internet-enabled device, (2) scrolling in “downtime,” and (3) “anxious compulsive checking” that often led to scrolling.

Despite how addicted I was to my phone, when I was fully engrossed in an activity—like writing, catching up with a girlfriend over coffee, or on a date with my husband—I honestly wouldn’t feel the urge to check it. Three or four hours would pass easily without it. (This is why I thought the kitchen idea would work.) My issue is constant proximity to a handheld, internet-enabled device. When all it takes is the touch of a finger to bounce between various apps, compulsively check social media, look something up, or impulse-buy something from Sephora—I will do it. And, of course, I took my iPhone with me everywhere.

My other issue is scrolling, particularly using “downtime” moments where I “have nothing to do,” and filling that time with my phone. Waiting for the train, riding the train, waiting for my coffee order to be ready, sitting at the doctor’s office, lying in bed before I fall asleep.3

I also suffer from compulsive checking, essentially an anxious behavior to see if things are still “okay.” It’s very hard to curb this when you have a smartphone (and you’re a new mom). If I felt anxious about something and decided to check it, I would often go on to check everything else. Sometimes these compulsive checks took less than 20 seconds, opening and shutting down the usual apps, almost unconsciously. Email, texts, calls, Instagram, Substack. Other times, I would get sucked in, which is, of course, the problem.

A note on social media and “logging off forever”

I completely understand why someone may wish to delete their social media accounts, because they feel a compulsion to check them constantly or because seeing other people’s greatest life moments make them feel badly about their own. I’m not terribly active on social media, and my friends and I are good at keeping up with each other offline. I’m also in my 30s, and social media just matters less as you get older.4

Because I have a baby, I physically cannot sit at a desktop computer all day browsing the internet, and I basically only get to go on my computer when my son naps. (As any mom knows, when the baby is awake, you’re busy, and when the baby is asleep, you’re busier.) Besides, I don’t want to log off the internet forever. There’s a lot I enjoy about it.

My problem is not having access to the internet, it’s having access to the internet at all times, wherever I am, no matter what else is happening.

In fact, having free access to the internet, and not swearing off social media entirely, has been key to my success in downgrading. Nuclear take: having Instagram is actually fine. I have limitations around my use of these platforms, but I still, crucially, am able to use them—just not immediately. It’s a bit like trying to eat better. I personally always have ice cream in my freezer and a box of shortbread cookies in the pantry. If I feel like dessert, I have some. But denying myself dessert entirely gives the “bad food” too much power.

It is a privilege to be able to downgrade, and my situation is somewhat unique.

A lot of people cannot downgrade their smartphone because they depend on it for their livelihood. I work from home, and can therefore check emails and messages on my computer. While I have held corporate jobs that essentially require constant monitoring of email and Teams/Slack messages, even outside of working hours, I do not have one now. This also means I am not bound to an ever-changing, back-to-back, double-booked calendar, which would be very hard to manage without a smartphone.5 (Though, when you’re at the office, this can be done on your computer.)

In terms of getting around, I walk, drive my car, or rely on public transport. I basically never take Ubers (and in NYC it is still possible, though not always reliable, to hail a cab).

Finally, I am also married, and therefore not using dating apps or social media to “meet someone.” In fact, very little of my social life happens online. When my friends and family want to speak to me, they call me or text me. People are also understandably less spontaneous with plans when they get older and have families, so I’m not torching my weekend plans if I don’t get back to someone immediately.

I do keep a “backup phone.”

My iPhone is not in the trash can. However, it is turned off 99% of the time and stored away in my filing cabinet at home.

I only use it for:

Driving to locations I’ve never been before, or on long road trips (for Google Maps + CarPlay + music). When I arrive at my destination, I turn it back off.

Domestic and international air travel - rare.

Essential QR codes + tickets I cannot print at home - rare.

Dual-factor authentication - I try to send codes to my email when possible.

Depositing paper checks - I technically can do this in person at the bank, but with the baby it’s kind of a drag.

Emergencies – if my flip phone is lost, stolen, or broken.

Keeping an iPhone also allows me to communicate with people via iMessage on my desktop using my old number. Everyone who has my iPhone number before I downgraded can still text me the way they always did. I just won’t respond immediately (though I didn’t always do that before).6 I think this has been an essential part of my success with downgrading: no one else in my life really feels a change. I still text people the way I always have, and if they need to speak with me urgently, they can call or text the flip phone number, which I’ve asked them to think of as a “work line.” It’s just a different number to call if you need to speak with me.

No one has had a problem with this, and most people actively encouraged me or said they’d been wanting to try something similar.

Downgrading to a flip phone immediately solved all three of my aforementioned problems.

(1) I am not proximate to a handheld, internet-enabled device. I am proximate to a phone, used for texting and calling.

(2) There is no scrolling on a flip phone.

(3) There is nothing to compulsively check. I can check my texts and calls, but that’s it.

Ok, but what about emergencies?

This is part of the reason I kept my iPhone as a backup phone, especially now that I’m a mom. If I needed to get somewhere urgently in my car, I want to use Google Maps + CarPlay. And if something happened to my flip phone, or I lost it, I’d still be able to use my iPhone.

That said, in an emergency, people tend to call you or you will call them. My flip phone does this just as well as my iPhone. God forbid I ever have to dial 911, but I can obviously still do this.

How does it feel to downgrade? What flip phone did I buy and from where? How did I tell my friends and family about my experiment? And what do I do for photos, maps, music, and everything else?

Writer and friend

suggested I kept a diary about my downgrading experience. It was a great idea. What’s it like to live without a smartphone, week by week?