Often I yearn for campus

Fall, nostalgia, νόστος, ἄλγος

Yesterday marked the first beautiful fall afternoon here in New York City. The brutal, and frankly, absolutely revolting humidity of late August and early September has finally broken, and the air feels clear and dry. The quality of the light is ever-so-slightly different now than it was in August, a bit yellower, with steeper shadows.

In September, the city feels like a fresh notebook, and there’s pretty much nothing I love more than a fresh notebook (Leuchtturm1917, 120g paper, off-white, dot grid, black cover; I literally tremble at the potential). Fall is the season for fresh notebooks, fresh air, fresh haircuts, fresh fits. That’s the “back on campus” feeling. When that feeling hits—and I should say, it’s not just fall, watching the first snow while languishing in bed with a novel does the trick, too—I feel an urge to do one of two things: buy a bunch of books I will probably never read for a syllabus I made up in that very moment, or fire up my fountain pen and kind of go off. (Yeah, yeah, yeah, I write with a fountain pen. I’m that kind of person, and honestly, I’ve come to terms with it. This should come as no surprise as I also carry a briefcase, which a waitress referred to, just two nights ago, as “sexy business,” much to my tremendous relief. Someone gets it, I thought to myself. Maybe I’m not so terribly alone in this life.)

To me, “campus” is about as perfect as a place can be, though, of course, I don’t miss everything about it. I don’t miss drinking jungle juice or begging to borrow my friends’ bandage dresses and heels for some fraternity date party where I would inevitably go back and forth with a group of what are essentially drunk children, quoting American Psycho. (“Don’t wear that outfit again.”) I distinctly remember a moment during my Sophomore year—I was between sips of lemonade Four Loko in a rotten fraternity basement—and I thought to myself, “Alright, so how much longer are we all going to do this, really?”

The truth is, I’ve never cared much for co-eds, even when I was counted among them. Ever since I was a little girl, I couldn’t wait to be a real grown up. When my parents hosted dinner parties with their thirty-something-year-old friends, I disdained being relegated to the dreaded kids’ table, surrounded by idiotic children like myself, eating sliced hot dogs with my fingers like a fool. I always preferred the company of intelligent, worldly adults who perhaps offered me a taste of their wine, allowing me the wonderful opportunity to perform my disgust for their amusement, and ideally, in my mind, ingratiate myself so that I may join them. Unfortunately, this was all in my head. Best case, they merely tolerated my presence, and most likely, I was extremely annoying and they saw right through my little act.

All that is to say… I don’t really miss college, or as I like to think of it, “the youthful reverie of low expectations.” I do miss campus (the place). And that’s because campus is a fleeting four-year taste of a place that limits and expands your life in all the right ways and is, generally, an antidote to the chaos of modern life.

For most Americans, four years of “being on campus” are the only opportunity we have to live in a real, tightly-knit community. (I’ve written about how isolating modernity can be here, here, and here.) The “real world” is insanely chaotic and everyone is always “soOoOo busy.” On campus, everyone is doing the same thing, more or less: you’re all rooting for the same team, you’re all going to class, you’re all on the lookout for potential romantic partners. Everyone is aligned, everyone is learning, everyone is horny. Need I say more? There’s a general routine, a certain predictability, and that can be such a difficult thing to cultivate in adulthood. (You really have to put some effort into it.)

Also—and this is huge—there are only a few places where you can hang out. Where I went to college, there were a few main buildings, maybe six good restaurants, a couple cafés in which to work, two main libraries, the sorority house, a big grassy field, and that was kind of it. As a result, we saw each other all the time, in spontaneous, unplanned, casual ways. Campus is highly social, but the real world doesn’t easily offer this kind of infrastructure. I’m sure you’ve heard about the study—and sorry, but I’m too lazy to look it up—that seeing a neighbor, having little exchanges with people you know, has the same effect as antidepressants. Whatever it is, it’s something like that, and I buy it.

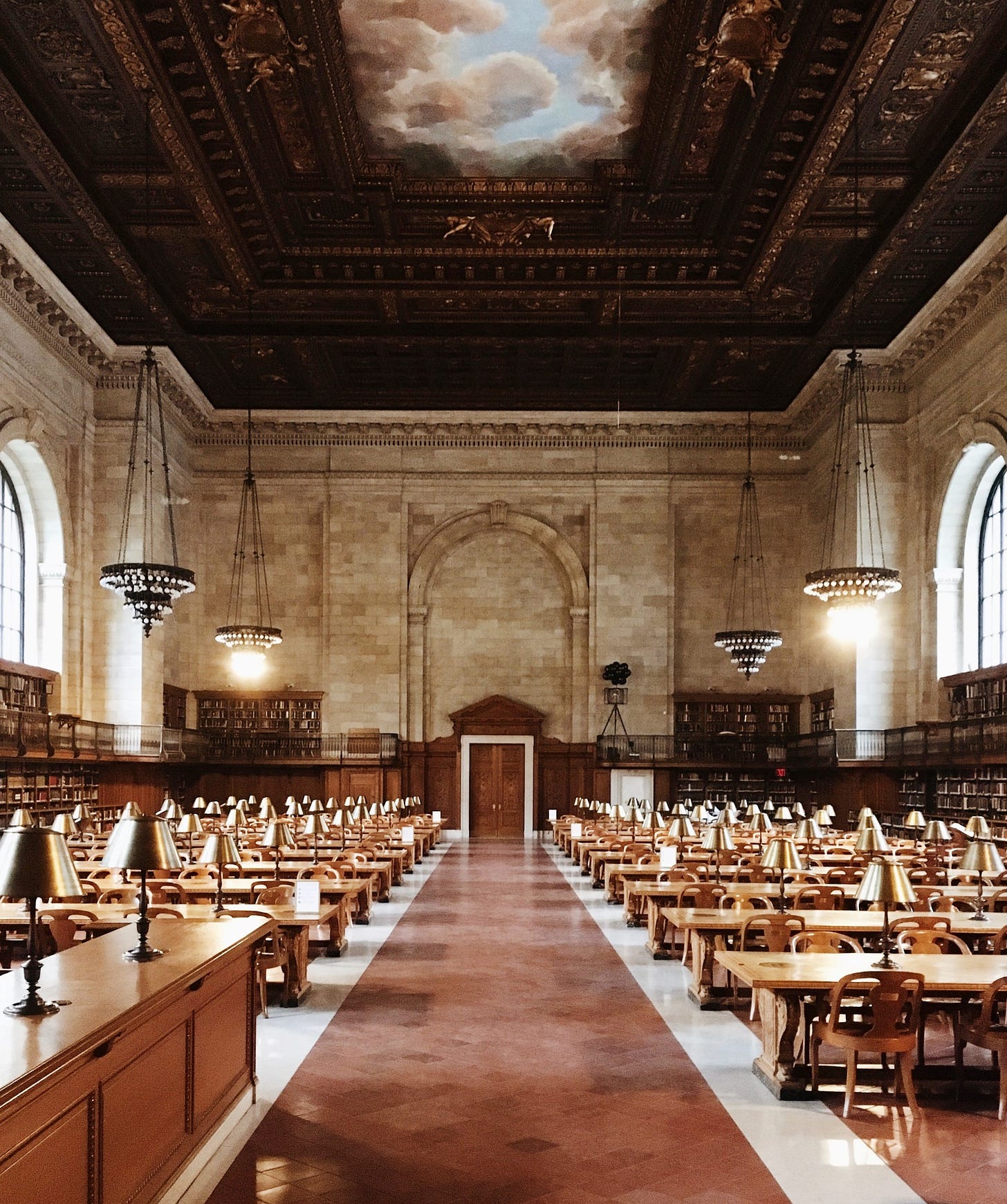

Once you’ve lived in New York City for a few years you’ll have your go-to places, sure, but there’s usually a transaction involved, sometimes several, and the whole thing needs to be planned meticulously into your day. You need a booking, a reservation, what feels like a hundred dollars. And if you don’t want to spend money? Best of luck to you. There are vanishingly few calm, communal, free spaces in New York City. The Rose Reading Room on Fifth Avenue is perhaps the closest thing I can think of, and it’s spectacular, but there’s only one for all eight million of us.

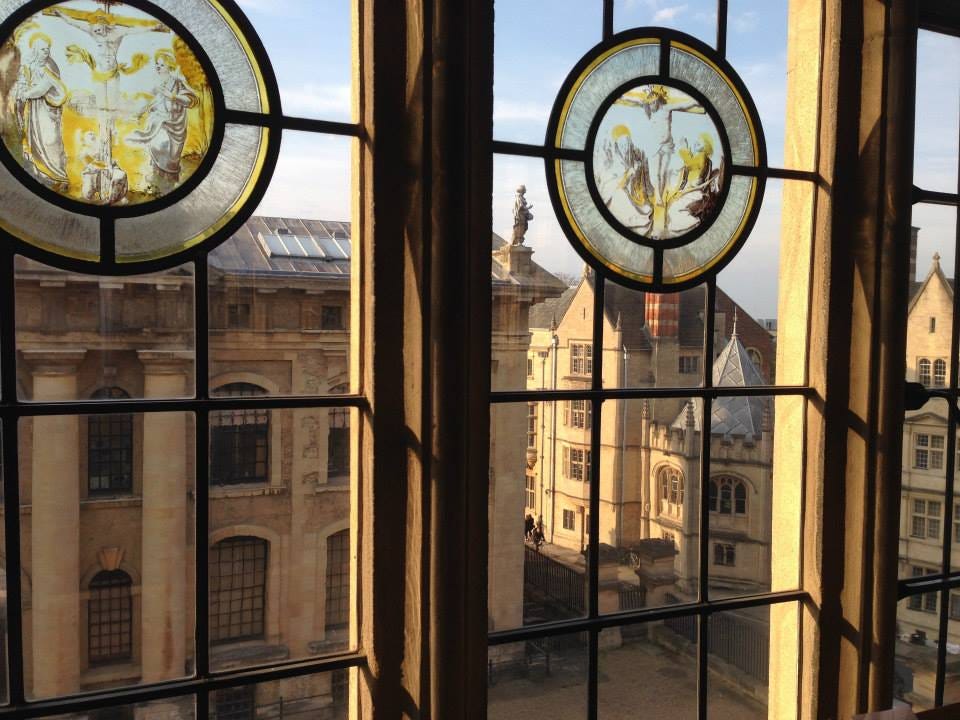

The Rose Reading Room is also beautiful, which is another thing I miss that is in short supply these days. Most college campuses are beautiful in some way, whether they have libraries adorned with marble Corinthian columns, embrace the natural landscape, or both. I studied Classics and could probably write a very tedious and boring essay about the beauty of classical architecture, how good it makes us feel, or the perfectly “human-centered design” of a plaza, but I’ll spare you. You can take my word for it. There’s a reason we gravitate to places like the library, The Met, and Central Park, but those places are not the norm. Most public spaces constructed these days aren’t places where you actually hang out for extended periods of time. Sorry, but I don’t consider Astor Place a place. It’s just a giant intersection.

But the real beauty of campus isn’t physical, it’s emotional. Campus is the place where the story begins. It’s the freshest notebook of fresh notebooks. Who you are, who you’re going to become, all of that remains to be determined. The potential is intoxicating, to say nothing of the alcohol and other substances that fuel the dreams of youth. Everyone around you is pushing themselves in every way—intellectually, socially, emotionally, physically. And not only is everyone striving, but they succeed. Being on campus puts you in proximity to greatness all the time: renowned professors and visiting speakers, the athletic achievements of your peers, the unforgettable parties, the inside jokes. It’s the best. I mean, who among us is totally immune to an atmosphere of prestige populated by handsome professors wearing thick sweaters?

No one is. Everyone loves it. So why does this kind of attitude—the feeling of searching, striving, growing—seem to fade away in adulthood? I mean, yeah, life gets more difficult in the real world. There are real problems and real responsibilities. We realize “the academy” can be as bureaucratic and banal as any corporate organization (maybe even more so). Aging brings its many disappointments. But we’re also much better equipped now, as adults, than we were back then. We know more about ourselves, what we like, who we are. Rather than merely daydreaming about our potential, like we did “on campus,” we’re given the real-world opportunity to take steps to fulfill it. But this agency has a strange tendency to backfire, and in the real world everyone pretends they already know all the answers, and acts like they know exactly how things will play out. Why do we tend to lose our curiosity as we gain more knowledge of life? It’s completely counterintuitive; usually, the more you know about something, the more interesting it becomes.

All of this got me thinking about the purpose of that “fall feeling,” and the broader purpose of nostalgia. The word “nostalgia” was coined by a Swiss doctor near the end of the seventeenth century to mean something like “the psychological pain of longing for the past.” Nostalgia is originally derived from two ancient Greek words. First, nóstos (νόστος), meaning both “the act of reaching a place,” and “the act of returning, or going back,” taken together, the journey home, the theme of Homer’s Odyssey. And second, álgos (ἄλγος), meaning “pain” or “sorrow.”

Nostalgia can be painful. Every September, I feel its tug. A part of me wishes I could go back and tan on the roof with my friends, walk to the library with my long, wet hair draped over my North Face backpack, furiously scribble notes during a history lecture, send off a term paper just in time to catch the party bus. But if I think about it a little harder, I realize how far I’ve come since then, how much more satisfied I am with my life now, and I know that I don’t really want to go back to those times. A part of me recognizes now what I failed to see then—how good I had it, how lucky I was, how I’ll treasure those memories for the rest of my life.

It’s easy to get tripped up, but we can’t let nostalgia be a stumbling block. We usually stumble over it in one of two ways: either we become trapped by nostalgia’s sentimental charms (never grow up), or dismiss nostalgia outright as silly and childish (please grow up). But to see nostalgia in either of these ways is to miss its purpose entirely. There would be no Odyssey if Odysseus never grew up, never left home, and he was not silly, weak, or sentimental to return. In fact, he gave up the option of immortality with a goddess in order to return to his wife and son. Ladies, if he wanted to he would.

Nostalgia, like intuition, is a guiding force. It is not a refuge from the world, but rather should inform how we envision our future. It shows us the two sides of life: what we have and what we lack. Nostalgia reveals both gratitude and longing.

We can’t go back. We’re too old now. But we get to remember, be grateful, and go on ahead. We may know more about life, but we can still be curious. We never have to stop striving. T. S. Eliot said it well: “Old men ought to be explorers.” And perhaps best: “We shall not cease from exploration / And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.”

In case it’s of interest, I’ve copied the full T. S. Eliot poems below. Both are from his Four Quartets (1943). “Old men ought to be explorers” is from East Coker V, and the other lines are an excerpt from Little Gidding V. If you want to hear these poems read aloud by T. S. Eliot himself, which I highly recommend, click here (starts at 3:12).