The Great Diminishment

Why things are getting worse but cost us more

My husband and I went to dinner at Metrograph recently with two of our friends. Over drinks, we were lamenting how everything feels so damn cheap nowadays. It’s not that we have limitless cash to blow on the really expensive stuff, but even if we did, so many of the “nicer brands” inundating our Instagram feeds are far too flimsy to justify the price tag. We recalled the mall brands of our youth, and how they pumped out higher quality clothing back then than we could find in the fancier parts of department stores now. Back in my day, the mall was the place to be, and J.Crew, Abercrombie & Fitch, and Diesel made good clothes. I guess you had to be there.

I still remember the Abercrombie corduroy jacket my parents bought me for Christmas in the early-2000s. That thing was built like a truck and I wore it every day for all of seventh grade. I still remember the tag inscription, written in cursive: “Abercrombie & Fitch | Authentic Quality.” It cost around $120 (a small fortune at the time), which translates to $188 today, adjusted for inflation. It would be literally impossible to find a jacket of that quality for under $200 at the mall today. (Those Aritzia coats might be the closest approximation, but they’re all over $300. And, sorry, I’ve owned an Aritzia coat, and the quality is just not there to justify the price. They look great out of the box, but quickly start to sag and look worn out.)

“Shop vintage” was basically the only answer we could come up with. And for clothing, that is the only way. You can “shop 90’s inspired denim” at the ironically-named Madewell for $138, or you can just buy the 90’s denim. It will be higher quality, cheaper, last longer, and perhaps most important: you’ll look better.

It’s not just fashion, of course. The Great Diminishment is happening in all the areas that make life worth living: entertainment, books, music, restaurants. Even things like furniture, architecture, and services like airline travel have gone downhill in the last two decades. I’m old enough to remember when airlines used to provide a hot meal on a domestic cross-country flight. Now they throw a single 70-calorie bag of Sunchips at you and expect your serf-like gratitude. Room & Board will gladly charge you nearly $4,000 for a wood veneer credenza. You almost have to admire the audacity.

Discerning millennials and older generations have pretty much resigned themselves to the fact that things are better when they’re older, or “vintage,” because they were made with craftsmanship and care. There used to be things of “Authentic Quality,” and you can still find them second-hand. It’s not at all pretentious to admit that film is far superior to an iPhone camera. (iPhones take bad photos… This is a conspiracy theory I am interested in…) Wired headphones have better sound quality than AirPods. Hardwood floors are infinitely better than slick, soul-crushing laminate imitations. Pre-war apartments are generally better than new construction. The Sopranos was one of the first great television series, and, arguably, has yet to be beaten.

Those of us who remember can look back and be nostalgic. We remember the pre-internet world. We can seek the old. We can say, “back in my day.”

But there’s a gap forming for Gen Z that depresses me. This is a generation that never knew anything but the way things are now. (A Gen Z colleague didn’t believe me when I told her about meals on cross-country flights.) This is a generation that’s being force-fed Dua Lipa blasting in their ears at an overpriced birria-tacos-and-ramen-mashup-pop-up spot, wondering why the world feels hollow. I want Gen Z to know that everything in life doesn’t have to feel flimsy, plastic, and grey. That’s The Great Diminishment at work. That’s not how life needs to be.

The hard cause: the “venture capitalization” of culture

The Great Diminishment has several causes. (The internet, social media, apathy, etc., all play a role. I’ve written more about how “everyone is numbing out.”) But a big cause is what I’ll call the “venture capitalization” of culture, where as much cost is squeezed out of every nook and cranny as possible, while prices remain the same or higher. You can’t get exponential growth out of finite resources and a plummeting birth rate. But you can squeeze the margins, make things a bit worse, hope no one notices (they will), and charge people the same or more. On paper, this will look like growth, but it is not. The really sad part is that this race to the bottom creates market conditions that cannot support things of quality or originality. It is no longer economically feasible; the business case isn’t there. (I’m sure I can thank the dry optimizers at McKinsey & Co. for the miniature bag of Sunchips. Well done, guys, really. Amazing work.)

Another example: I recently got around to watching Heat (1995, dir. Michael Mann starring Robert De Niro and Al Pacino), and it’s a great movie for many reasons, but one that stood out to me was Dante Spinotti’s cinematography. Guess what movie he was recently hired to do? Ant-Man and the Wasp. Isn’t that terrific. I’m sure Dante laughed all the way to the bank, but I’m not sure if Hollywood is even capable of making a movie that looks like Heat anymore. I sincerely hope someone out there is trying. If not, the artistry will die out.

Don’t take my word for it. We’ve been here many times before. After the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 A.D., people literally lost the knowledge for building domed structures like the Pantheon, which was completed in 125 A.D. For centuries, these buildings loomed as mysterious monuments from a forgotten civilization.

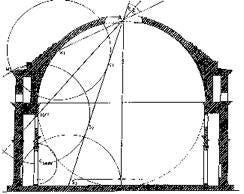

It wasn’t until nearly a thousand years later, in 1414 A.D., that documents were discovered that outlined the ancient technique for making cement. A new interest in the classical age, and classical techniques—The Renaissance—was well underway, and the great architect Filippo Brunelleschi constructed the domed roof of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence (colloquially known as “The Duomo”) just a few years later, between 1420 to 1436. To this day it is considered a masterpiece of European architecture.

I hope we don’t have to wait a thousand years for another car chase scene that looks like the one in Heat, or a classic, feel-good rom-com like 13 Going On 30 (2004), which unapologetically delivers the message: don’t worry so much about your career and focus on your family and the people who have loved you since the beginning. What a concept.

The soft cause: the loss of respect and dignity

But the real root of the problem is something much deeper than cost-cutting exercises, maximizing shareholder value, and a general loss of craft and bold originality. Somewhere along the way, we lost respect for each other. We’ve broken our social contract, forgotten our manners, ignored the golden rule. The producers have lost respect for the consumers. They’ve lost respect for the audience, the customer, you. The producers value the thing itself, its stock price, its popularity, the clicks it drives, the margins it creates, far more than your experience of the thing. This is a problem.

Why is this happening? Well, this phenomenon is certainly not new. It’s been happening for a long time, possibly even forever. This is happening because the materialistic world we live in not only values things more than people, but treats people as if they were things. And it does this with cool, calculated indifference, always in service of its own ends.

Things are tradeable, marketable, interchangeable, standardized, measured, counted, weighed, ranked. Things are great for corporations and corporate power. Not so for us, our friends, and our families. We must remember that people are not things, no matter what the world tells us. (This is especially true in the age of AI.) Yes, we must seek excellence, quality, and craftsmanship wherever we can. We must also shun the flimsy, the plastic, and the false. But most of all, we must refuse to be diminished, to be made small and unimportant, reduced to a number in a spreadsheet or a line of code. We must see others, and ourselves, as worthy of respect and dignity. A machine—a thing—is not capable of either.