It is seldom wise to tell all

Notes on disclosure, discretion, and the intimacy of language

The Department of Homeland Security commands it: If You See Something, Say Something. You are expected to “tell your story,” “bring your whole self to work,” “share your superpower”1 to kick off the kickoff meeting. The mindless chatter is incessant. The Podcast Industrial Complex churns on. The volume of writing is enormous in quantity, dithyrambic in tone. Left, right, and center, the discourse is unrestrained and hysterical. Many a New York City resident should be involuntarily committed to The Internet Hospital with a feverish case of the hot takes. In a world that demands nothing less than total disclosure, many cave.

Few among us wield the cool power of tactical silence.

Now, I’m not advocating for always saying nothing, which would be rich coming from someone whose every conscious thought has a prologue, an epilogue, and several footnotes along the way.2 I'm reminding you—reminding myself—that we always have that option. You have the right to remain silent. It’s easy to confuse personal exposure and self-disclosure with confidence, spontaneity, vulnerability, or brilliance. We could probably all benefit from more modesty, secrecy, and discretion. I mean, it’s called your personal life for a reason.

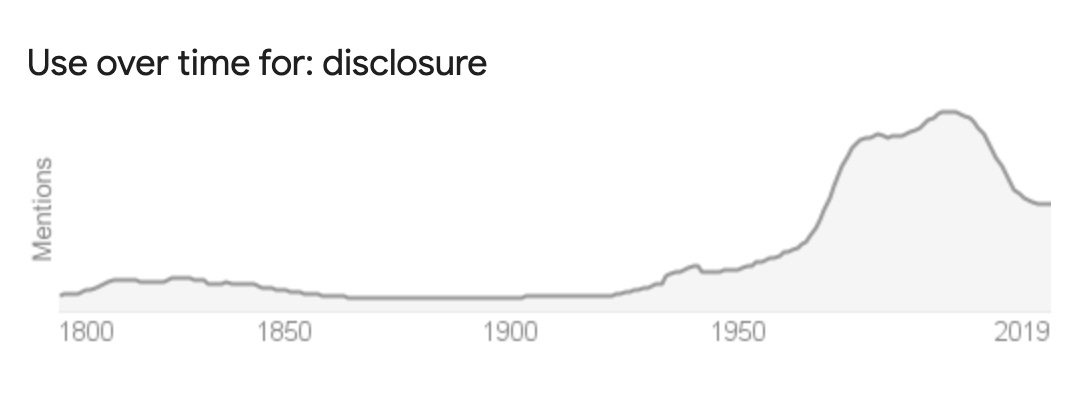

Discretion used to be the default mode of social engagement, but no one talks about it much anymore. Discretion has two definitions: first, “the quality of behaving or speaking in such a way as to avoid causing offense or revealing private information,” and second, “the freedom to decide what should be done in a particular situation.” The words discretion and discern share the same Latin root discernere (to separate, set apart, divide, or distinguish; or figuratively, to determine, settle, except, omit). Discretion is required to discern your vocation, or reflect on your interests, values, and skills to understand what you’re meant do with your life. Acting with discretion is an interior, silent process. But it is also a freeing one. We can think of discretion as an internal compass of sorts that separates or distinguishes us—going back to the Latin—from the chaos all around us.

Discretion is something that the vast majority of human beings, for the vast majority of human history, knew all about. We used to truly know our neighbors (and not just our neighbors, but their parents, their children, even their colleagues). People’s actions and speech had immediate, real-world consequences instead of the vague threat of online cancellation. In this arrangement, privacy was highly valued. People already knew a lot about your life, so you didn’t want to allow excessive access to yourself.

“Speech is silver; silence is golden.”

—9th century proverb

Nowadays, odds are, no one living near you knows much about you. My former so-called “neighbors” in the East Village probably didn’t care if I lived or died. In the modern arrangement, everyone gets the same even-handed treatment. Strangers, haters, acquaintances, colleagues, friends, and family all see the same Instagram story. It’s arguably not enough intimacy for friends and family, and it’s certainly too much for everyone else.

But forget the closeness of a tightly-knit community to soothe our aching hearts. Most of us will settle for something far more basic: evidence of our existence. Talking about ourselves is one way to prove we exist. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in the parasocial pseudo-intimacy of the influencer economy. When I see an influencer document every meal, every outfit, every experience—no matter how mundane—I see someone trying very hard to prove to the world that they indeed exist. When you spend your whole life getting torn apart in the woodchipper of online media, there’s no stepping back and seeing the forest for the trees. Life and its experiences are mere logs, all destined for the chipper, to be used up and consumed. This materialist approach unfortunately trickles down to the rest of us. The classic philosophical thought experiment, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” could be re-written today as, “If no one but me witnesses my life and experiences, does my life even matter?” In our modern age, if things don’t happen publicly, for an audience, we cease to believe they happened at all.

This is brutally disempowering because it puts the locus of control, validation, and joy completely outside the self. Discretion was the compulsion for nearly all of human history, so when people started speaking out, it felt wildly liberating. I’m not denying that, or that it can still feel liberating now.3 But we’ve swung very hard in the other direction. The new compulsion is to always say something, have an opinion, and pretend to know the answer. Allowing yourself to say nothing can set you free. Maybe you’re not an “extroverted introvert,” you just understandably want both a social life and to maintain a certain distance between your deepest self and the uncaring world. If no one ever told you that your private life and your innermost thoughts are not just valuable, but precious—allow me to be the first. You can be a private person without selfishness, guilt, or shame.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with grappling with our deepest thoughts, fears, and sorrows privately (this of course can include our closest friends and family within the private sphere). You don’t have to constantly explain yourself. It’s okay for people to be wrong about you. Let them. No amount of explaining or caveating will change their mind.

And besides, there is something fun about having a few secrets and keeping things to yourself. Don’t repress your thoughts and feelings—keeping a diary is great for this—but consider going Mona Lisa Mode. Let the world wonder what you’re thinking.

It’s also easy to conflate prattle with passion. Creative types often discuss returning to the “child mind” to force themselves to see things with fresh perspective and work in a spontaneous and uninhibited way. But they more often forget—or, more likely, just don’t know, especially if they live in New York City—how small children actually behave. Children see everything and say nothing. Like all artists, who create great works in the wide open spaces of solitude, a baby is perfectly content in her silent exploration. When a child does speak, she’ll often ask disarming questions—from the most banal to the most existential. Once upon a time, this is how each of us learned about the world around us. We are given the personal gift of quiet contemplation years before we are given the shared gift of language. Perhaps, in our attempts to return to a purer state of mind, we should heed the classic warnings of our parents. Look both ways before you cross the street. Don’t tell people where you live. Keep it to yourself. Leave something to the imagination. Hold your tongue. I’ll be the first to admit that my writing got a lot better when I learned to edit myself and realized that my every passing thought is decidedly not of general interest.

Even though we don’t act like it, there is profound intimacy in language and conversation. In writing and speaking, we grant access to our time, our thoughts, ourselves. Our words, once spoken, can be forgotten. But they can never be taken back. Reckless disclosure devalues the self; discretion respects it. Still waters run deep.

Please, dear employee, tell us how best to exploit you. (To say nothing of the Marvelification of modern life.)

Lifelong sufferer of OBS (Open Book Syndrome).

There’s plenty of confessional writing here on Substack, and I take absolutely no issue with it because it is thoughtful writing, not shoot-from-the-hip hot takes, or, God forbid, short-form videos with that distinct and profoundly irritating “trying to go viral” voice. I genuinely enjoy confessional writing, and often it helps me find the words I struggled to find on my own. But don’t let the confessional nature of it fool you, the reader. Before the author shared this particular part of their life with you, they sat quietly with themselves, in silence, often for many hours, and thought hard about exactly what they wanted to say.

I work in marketing (boo, hiss) and have frequently had to remind my coworkers that our company not only has the ability to say nothing, but often the responsibility to do so. In am era where we are subjected to everyone's take on everything, all the time, it is incredibly refreshing to hear someone advocate for discretion! I also think there is something to mourn in the substitution of "having a personal brand" for having "character" because as you so eloquently outline, branding requires witness; character is who you are/what you do when nobody is watching.

loved this so much, so beautifully put. phone accessibility + the boom of social media apps gave everyone, even thing (aka business and brands) a voice that almost feels forced. we don't nearly sit with our own thoughts enough bc there's always someone out there that "needs" to hear this take or idea.

i've been thinking a lot about discernment and discretion lately especially when it comes to having ideas as a creative writer or artist. i wrote in my journal "some ideas just need to go on vacation" they don't need to be unearthed yet even if it sounds so new and seductive to implement - they need to just sit and breathe and we can see if they take a different form later or come back to it if it hasn't.